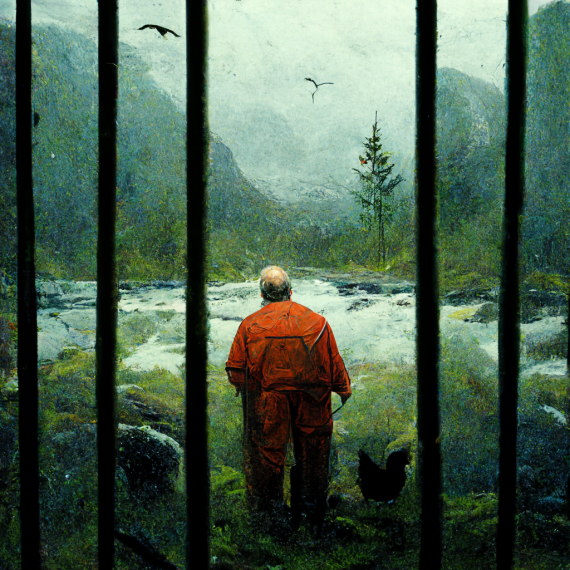

In recent years, the concept of “healthy prisons” is increasingly used to highlight the possibility of a health-promoting environment fostering the physical, mental, and social well-being of people in prison. To delve deeper into the notion of a “healthy prison”, I conducted interviews and ethnographic fieldwork in two low-security prisons deliberately selected for their potentially health-promoting elements. During my fieldwork, two of the selected prisons (Prison A and Prison B) were impacted by a number of challenges or disruptions, changing the daily routines for prisoners as well as staff. The data shed light on the impact disruptions can have in a prison, and the importance of staff-prisoner relationships in an environment aiming to be health-promoting.

The Covid-19 pandemic reduced the sense of stability, predictability, and security in prisons all around the world. Austerity measures, in the form of economic constraints and stricter rule enforcement, also contributed to noticeable changes. However, Prison A experienced several additional disruptions in the work environment compared to Prison B, such as workplace conflicts leading to internal grievance cases, several tedious rounds of organizational restructuring, and high staff turnover. These overlapping disruptions were difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish from each other.

Data from both fieldwork and interviews revealed a noticeable reduction in the quality of staff-prisoner relationships in Prison A, and many pointed to several of the disruptions as reasons. Positive relations and trust between staff and prisoners are key elements of dynamic security, which both prisons rely on, and these qualities were noticeably reduced in Prison A compared to before the disruptions begun. In contrast, Prison B continued to enjoy an unusually (compared to other prisons) positive staff-prisoner dynamic, despite ongoing disruptions.

While both prisons experienced unpredictable changes due to these disruptions, the degree to which prisoners perceived these changes as legitimate varied. Perceptions of the cause or purpose behind unpopular changes varied among prisoners, and prisoners directed blame towards different organisational levels of the prison system. Prisoners in prison A frequently interpreted changes as a type of punishment implemented by the prison staff, instead the results of decisions made at a higher level of the organisation. Prisoners in prison B, on the other hand, blamed a higher system level, making it appear as an external challenge the prisoners and prison staff faced together, enabling a continuing positive staff-prisoner relationship.

In addition to the aforementioned temporary disruptions, there is another important distinction between the two prisons. Prison B is significantly smaller in terms of the prison population and the physical size of the prison area. Most prisoners and prison staff are located in one main building. These differences became evident during the pandemic. When informal meeting places were closed down, the physical, and thus the relational, distance between staff and prisoners was increased.

These preliminary results thus indicate two things. Firstly, prison size affected the impact these disruptions had on the prison environment. Secondly, not even presumably “healthy” or exceptional prisons remain unaffected when faced with unexpected challenges or disruptions.

About the author

Pernille Nyvoll is a PhD scholar at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of law at the University of Oslo. Her PhD project is part of the PRISONHEALTH project.