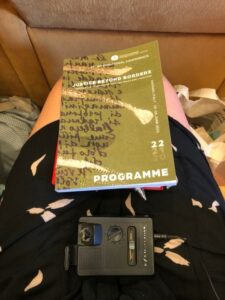

In June 2022, I participated in my first international conference as a PhD fellow, organized by the European Forum for Restorative Justice (EFRJ). It took place in Sassari in northern Sardinia, Italy. Here, around 350 academics and practitioners of restorative justice from 41 different countries gathered to present, discuss, and form relations concerning restorative practices in criminal matters.

The venue that the organizers had chosen was located slightly uphill from the city centre. With a view of the city rooftops, side-by-side with one of the many catholic churches in Sassari, a metal gate revealed the words: “Conservatorio di Musica”.

A broad cobbled staircase showed the way up to the classical music conservatory which consisted of pink chalk painted buildings that surrounded two small courtyards. When I arrived with my colleagues from the Aarhus University-based research project, Konfliktråd Impact Project (KIP), the place was already buzzing with people. Name tags around their necks and tote bags over their shoulders, ready for three days of conferencing.

Let me briefly introduce my PhD project and how it relates to restorative justice. In brief terms, my project is an anthropological investigation of the Danish victim-offender mediation programme (Konfliktråd in Danish). From the perspectives of people charged with violent crimes, I seek to cover the interplay between their legal case proceedings and their participation in Konfliktråd. How are these simultaneous processes connected to their social relationships and their sense of self? What happens to a person when they become “a violent offender” in the eyes of others as well as themselves?

Victim-offender mediation (VOM) allows the offender and victim of a crime to meet and discuss the offense with a third-party mediator (Kyvsgaard et al. 2018:23). Both academics and practitioners denote VOM as an example of a restorative justice process, along with other variations, such as Restorative Justice Conferences and Circles. While the concept of restorative justice has a quite intricate and contested history (e.g. as illustrated by Gade 2018), it is popularly used to describe an approach of responding to harm which focuses on repairing the damage and restoring the dignity of those involved (EFRJ, Marshall 2011).

With my project, I have set out to investigate how such is practiced in the Danish Konfliktråd and how this process is experienced by the people participating in VOM as the “harm-inducers”.

On the first day of the conference, I partook in a presentation by Leanne Trapedo Sims which concerned imprisoned Hawaiian indigenous women, or insiders, as she liked to address the women she worked with. Among other things, the project concerned the women’s perceptions of home and how they expressed these through poetry. Approaching her work through a post-colonial lens, Sims perceived the prison as a landscape of oppression and, to a high extent, her interlocutors as victims of structural violence targeting the indigenous (in this case, female) population in Hawaii. One of the poems written by a woman inside went as follows:

The reality of my life today

I made all on my own

If I could change one thing in life

I would have stayed home

As I read this excerpt during the presentation, it got me thinking. Even though this woman is exposed to oppressive structures, she clearly believes that she is responsible for the position that she is in. She frames it as her own fault that she has spent more than a decade in prison. She could potentially have chosen otherwise – she could have chosen to stay “home”.

I am particularly curious of perspectives like these; the experiences and inner life of people charged with violent crimes, and how they take form through their structural, social, political, and narrative dynamics. Through long-term anthropological fieldwork and deep immersion in all aspects of my interlocutors lives and thoughts, I will seek to obtain an understanding of what the “violent offender” experience can entail.

Bibliography

European Forum for Restorative Justice (EFRJ). Restorative Justice in a Nutshell. https://www.euforumrj.org/en/restorative-justice-nutshell. Last visited: 17 July 2022.

Gade, C. B. N. 2018. “Restorative Justice”: History of the Term’s International and Danish Use. In: A. Nylund, K. Ervasti, and L. Adrian (eds) Nordic Mediation Research. Springer. pp. 27-40.

Kyvsgaard, B., van Mastrigt, S., & Gade, C. B. N. 2018. Genoprettende retfærdighed og recidiv i Danmark. In: Samfundsøkonomen 4: 23–28.

Marshall, C. 2011. Justice, restorative. In: Green J. B. (ed) Dictionary of scripture and ethics. Baker Academics, Grand Rapids.

Clara Rosa Sandbye is a PhD fellow at the Department of Anthropology, Aarhus University. Her research interests concern issues of criminalization, violence, and morality. With her PhD project, she investigates how persons charged with violent crimes experience proceeding through the Danish restorative justice program (“Konfliktråd”). She is affiliated with the Konfliktråd Impact Project (KIP). Contact: clasa@cas.au.dk